Featured image: in Kyrgyz, “Бары алдыда” translates to ‘Everything is ahead‘

A few weeks have passed since I came home from a two month residency in Osh, Kyrgyzstan, but I am just starting to digest all the experiences that I had the chance to collect. This was my first visit to Central Asia and my already high expectations for the food, the nature and – not the least – the people I would meet, were far surpassed. I made new friends, overate on borsok, climbed mountains, and gained invaluable new perspectives from Novi Ritm, the civil society organization that hosted my residency. When I look back, I realize that my two months are full of memories, and new outlooks and insights.

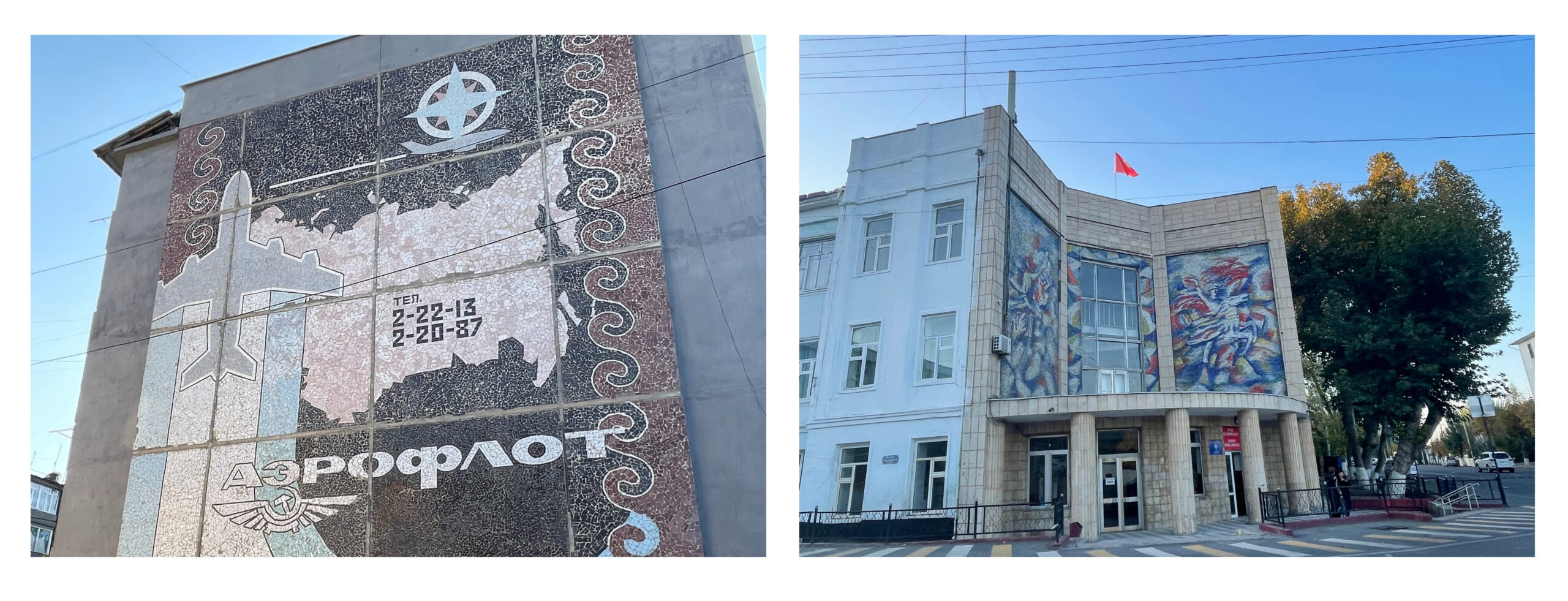

Mural artwork in Osh

I remember one Thursday when the crisp evening air confirmed that autumn had arrived in Osh. Pumpkin samsas were baked in each street corner and the sunset cast a golden hue over the city. We met in the office to rearrange the furniture and organize the documents stored in the staff room. The shelves bore witness of activities that have taken place over the past years, and creative artwork peeked out between an old computer screen and a pile of dictionaries. New projects were in their start-up phase and several new staff members were just about to take office. It was truly a season of change for Novi Ritm.

Outside the office walls other changes were taking place in Kyrgyzstan. Just a few couple of years ago Kyrgyzstan was seen as a representative of positive development and democracy in Central Asia, but this perspective is changing. According to democracy rankings the situation in Kyrgyzstan has deteriorated over the past few years, and from being considered a hybrid regime in the EIU Democracy Index the country has fallen below the threshold and is now seen as an authoritarian regime. The parliamentary elections 2020 was surrounded by accusations of electoral fraud, and after widespread protests the electoral authority declared the results to be invalid. Following the election, a constitutional referendum was held in April 2021 resulting in Kyrgyzstan abandoning the parliamentary system that had been in place for ten years in favor of a strong presidential system.

Democratic deficits in a constitutional system often have spill-over effects on other parts of society. In Kyrgyzstan this is apparent in different ways, challenges in press freedom and corruption levels are two examples. Independent media channels have faced backlash, some have been blocked, and journalists risk being threatened, abused or imprisoned. The lack of independent media is especially harmful to young people as they are more susceptible to fall for misinformation. Corruption, a factor that is often less present in countries with strong democratic institutions, also appears to have an increasing stronghold in the country. After a steady improvement of its score between 2013 and 2020, Kyrgyzstan fell twenty places in Transparency International’s Corruption Index for 2021 and remained on the same low in 2022.

When we finally sit down for dinner after a day of rearranging the office and moving the staff room, one of the girls glances through the notifications on her phone before she looks up and asks us “Did you hear it yet? Today they decided on allowing the president to overturn court rulings”. She refers to a decision taken by the Kyrgyz parliament, the Jogorku Kenesh, earlier the same day that would allow the president to revise and overrule decisions taken by the constitutional court, and as such, fully abandoning a parliamentary system based on rule of law. A sense of disbelief is felt around the table, but they ensure me that they are not surprised by this outcome. The developments over the past years have all been clues of the direction towards which Kyrgyzstan is currently heading.

In view of the democratic backsliding in the recent past, the role of civil society is pivotal. Civil society is a central building block to democracy and their role is now, perhaps more than ever before, critical for the development in Kyrgyzstan in the years to come. As an active youth organization in southern Kyrgyzstan, Novi Ritm plays a crucial role in upholding a democratic space. Several activities and projects are in place in order to foster youth engagement and encourage ownership of their activism. Discussion clubs on women’s rights and feminism are organized almost on a weekly basis, and seminars on youth participation and movie screenings on human rights-topics are regularly recurring. LGBTQ issues can be raised in safe spaces, and the bar to participate in the organization’s activities is low. During my time with Novi Ritm, I had the chance to participate in a various range of activities, and I am deeply grateful for all new perspectives that I gained.

Apart from the work being carried out by Novi Ritm, the office is in itself a tangible resource for the organization, as it provides a physical space where young people can meet. In the office building, young people come to share their perspectives, learn from each other and work together for a common cause. Everyone greets each other when they come and leave, and the sense of community is palpable. My time with Novi Ritm has shaped my understanding of how building democracy is not a linear process, but seeing the engagement of all the people that I met in the organization makes me convinced that even their smallest projects can have lasting effects on youth participation, and by extension, also the democratic progress.

/Miriam, Resident at Novi Ritm, Osh, September – October 2023